Discussions on Permanence (1/n): Economic Equivalence, PACT, Ton-Year Accounting, Article 6.4 Public Comments

This article is an automatically translated version of the original Japanese article. Please refer to the Japanese version for the most accurate information.

This is sustainacraft Inc.'s Newsletter (Special Edition). This time, we will discuss **durability** related to carbon storage.

Our company primarily deals with **nature-based projects** such as **REDD+** and **ARR**, which are temporary as carbon storage within the long carbon cycle (here, "temporary" means not permanent when compared to the timescale of fossil fuels accumulating or being emitted). The question of how to quantify the value of such temporary carbon storage compared to permanent carbon storage has been debated for a long time.

In this series, we will introduce the PACT (Permanent Additional Carbon Tonne)1 framework, which was recently proposed in the paper "Realizing the social value of impermanent carbon credits" by Cambridge University researchers, while also organizing the concepts proposed so far (*).

This article turned out a bit long, but first, I'd like to present an important question for you to consider. Given that "temperature increase depends on cumulative CO₂ emissions," temporary carbon storage that is re-released before peak warming makes no contribution from the perspective of "peak warming." However, any **Emission Reduction** or **Removal / Sequestration**, even if temporary, must be better than doing nothing. So, **how can something that is better than nothing have nothing to offer a policy target?**

how can something that is better than nothing have nothing to offer a policy target?

(Excerpt from Reference [1], introduced below)

(*) Originally, I had planned to introduce PACT in a single article, but as the introduction became lengthy, I've decided to publish it in several parts.

Here, "peak warming" refers to the timing when temperatures reach their maximum, which is generally understood as the time when **net zero** **Greenhouse Gas** emissions are achieved.

References

Given the number of references this time, I'll list them all at the beginning, though individual links are also provided.

- [1] A framework for assessing the climate value of temporary carbon storage (Carbon Market Watch, 2023 Sept): link

- [2] Unpacking ton-year accounting (Carbon Plan), link

- [3] Matthews, H.D., Zickfeld, K., Dickau, M. et al. Temporary nature-based carbon removal can lower peak warming in a well-below 2 °C scenario. Commun Earth Environ 3, 65 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00391-z

- [4] Accounting for Short-Term Durability in Carbon Offsetting (carbon-direct): link

- [5] Groom, B., Venmans, F. The social value of offsets. Nature 619, 768–773 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06153-x

- [6] Zack Parisa, Eric Marland, Brent Sohngen et al. The Time Value of Carbon Storage, 13 October 2021, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square [https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-966946/v1]

- [7] Matthews HD, Zickfeld K, Dickau M, et al (2022) Temporary nature-based carbon removal can lower peak warming in a well-below 2 °C scenario. Commun Earth Environ 3:65. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00391-z

(1) Introduction: A framework for assessing the climate value of temporary carbon storage

Before diving into PACT, let's introduce the underlying concepts by referring to Reference [1], published by Carbon Market Watch.

Atmospheric Lifetime of CO₂ Emissions

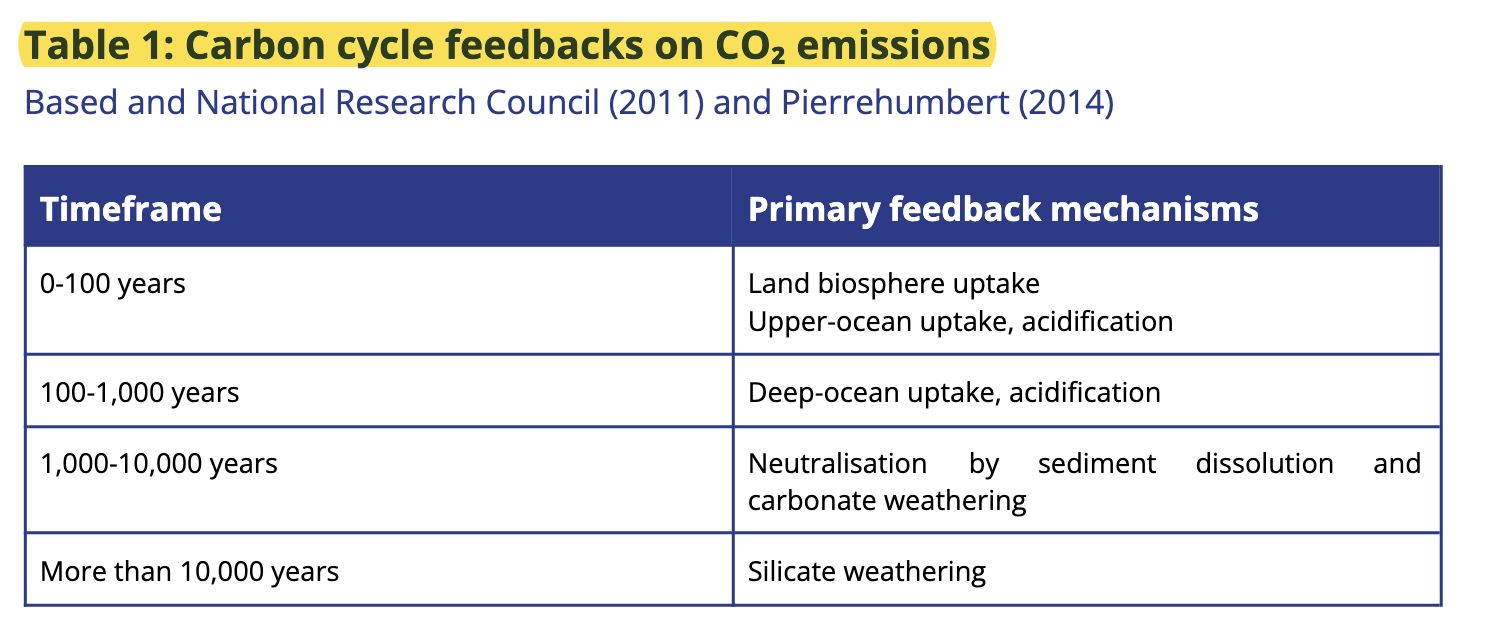

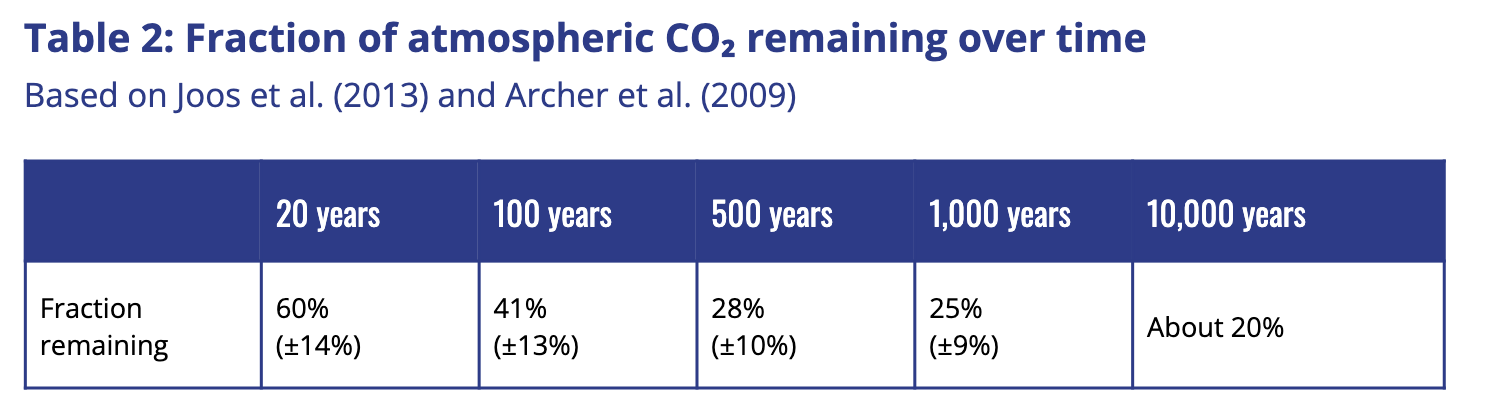

First, we must grasp the timescale of the carbon cycle. As shown below, carbon released into the atmosphere moves between the atmosphere, land, and oceans over a very long timescale. Most of the initial concentration is absorbed by the biosphere and oceans over decades to centuries, with significant uptake occurring rapidly within years to decades of initial emissions. After that, as the oceans and atmosphere equilibrate, it plateaus over centuries to millennia.

Impact on Temperature Depends on Cumulative CO₂ Emissions

Next, it's important to understand that temperature increase depends on the cumulative **Carbon Dioxide** emissions up to that point. The IPCC also reports the following:

(Canadell et al., 2021, p. 678)

There is a near-linear relationship between cumulative CO₂ emissions and the increase in global mean surface air temperature (GSAT) caused by CO₂ over the course of this century for global warming levels up to at least 2°C relative to pre-industrial (high confidence). …

Mitigation requirements over this century for limiting maximum warming to specific levels can be quantified using a carbon budget that relates cumulative CO₂ emissions to global mean temperature increase (high confidence).

This implies that the value of temporary carbon storage can reduce peak temperatures if its storage period is longer than the timing of peak warming, but otherwise, it does not contribute to peak warming. In other words, whether temporary carbon storage can contribute to peak warming **depends on the relationship between its storage duration and the timing of peak warming.**

Valuing Temporary Carbon Storage Against (Permanent) Fossil CO₂ Emissions

No method for carbon storage that is physically equivalent to emissions from fossil fuels within the aforementioned timescale has been established. This report notes that even Frontier, a procurement fund for long-term carbon **Removal / Sequestration**, generally uses 1,000 years of **durability** as a standard for its purchasing activities. It then states that this does not permanently avoid the impacts of warming, concluding that long-term storage and permanent storage are not physically equivalent.

As there is no solution with such **physical equivalence**, the value of temporary carbon storage is usually discussed based on **economic equivalence**, which assesses the expected costs and **Co-benefits** of carbon storage. "**Economic equivalence**" employs economic discounting, a perspective that places greater weight on short-term climate **Co-benefits** than long-term climate damages. This can involve ignoring climate damages after a certain point, or applying a compound discount rate to long-term climate damages.

While this introduction has been lengthy, how to advocate for this "**economic equivalence**" will be the main topic introduced in this article.

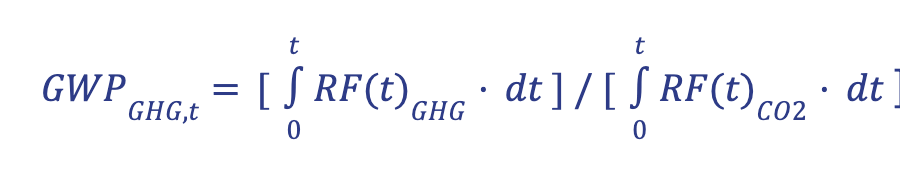

GWP (Global Warming Potential)

This is a slight digression, but here I'll discuss GWP, which is likely familiar to many of you. As you know, **Methane** has a **Greenhouse Gas** effect 30 times higher than that of **Carbon Dioxide**, and **Carbon Dioxide** equivalent (CO2e) values are used accordingly. The basic idea is to calculate relative values to **Carbon Dioxide** based on the cumulative radiative forcing, which is computed using the following formula:

The problem here is how far to extend t when integrating. While CO₂ has a virtually permanent effect on the climate, most other **Greenhouse Gas**es have a definite and relatively short atmospheric lifetime. Therefore, GWP does not reflect physical equivalence between two **Greenhouse Gas**es, but rather is a calculation result within a specific timeframe. Specifically, in the IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report, the GWP for **Methane** over 20, 100, and 500 years is 82.5 (±25.8), 29.8 (±11), and 10 (±3.8) respectively, showing that GWP decreases as the timescale lengthens2.

Tonne-year accounting

Tonne-year accounting3 is positioned as a method for valuing temporary carbon storage, similar to GWP, based on a radiative forcing approach. Regarding tonne-year accounting, an **Improved Forest Management (IFM)** **Methodology** based on it was proposed by NCX, so we have covered it several times in previous articles, such as the following:

While GWP is a framework for comparing non-CO₂ **Greenhouse Gas**es with CO₂, tonne-year accounting is a framework for comparing the value of temporary carbon storage with permanent carbon storage over a certain period.

In Reference [1], tonne-year accounting is criticized for ignoring losses after a certain time, similar to GWP, and for not considering effects such as albedo. It is known that trees and forest cover reduce the Earth's surface reflectance (albedo), thereby having an effect that increases temperature through a different mechanism than carbon storage.

For example, in Canadian reforestation projects, it has been reported that ignoring albedo leads to an over-crediting of approximately 16% for deciduous species and about 45% for evergreen species (Badgley et al., 2023). This study published in Science magazine also reported that for 448 million hectares of arid land identified using high-resolution spatial analysis, the carbon **Removal / Sequestration** potential until 2100 is 32.3 billion tonnes, but 22.6 billion tonnes of this are offset by albedo.

There are several approaches to tonne-year accounting, with the Moura Costa method and the Lashof method being representative. The Moura Costa method has been criticized for overestimating the value of temporary carbon storage. For differences between these methods, please refer to Reference [2] by Carbon Plan.

Approach Based on Temperature-based Damages

When discussing **economic equivalence**, the second approach, alongside the radiative forcing-based approach, is to calculate damages caused by temperature increase. Reference [1] asserts that this approach is superior to tonne-year accounting, but notes that by using discount rates, there is a possibility that scenarios that reduce short-term losses at the expense of long-term damages might be chosen. This could contradict the reduction of cumulative CO2 emissions, which is crucial for curbing temperature increase.

The argument that this approach is superior to tonne-year accounting is clearly stated in "The social value of offsets" [5]. On the first page, the following message was sent to the Supervisory Body of the UNFCCC **Paris Agreement Article 6 (6.4)** Mechanism:

We are very sceptical of the tonne-year approach which generates equivalence of permanent and temporary emissions reductions in a manner that ignores a) the latest climate science; b) the welfare economic aspects of the problem of temporary reductions; c) the risks associated with temporary projects. In particular Section 4.4 onwards. In the attached paper we provide an explanation as to why the approach discussed is problematic and we then offer a useful alternative that solves these shortcomings. While it could be said that our approach introduces controversial issues concerning discount rates, the previous contributions which focus on the physical measures of carbon make implicit discounting assumptions and assumptions about damages.

Multiple frameworks have been proposed for calculating damages from temperature increase. PACT, which will be introduced in this article, is one such framework, as is the one proposed in the aforementioned Reference [5].

We will delve into the damages caused by temperature increase in the next article.

Supplement: Public Comments on Removal Activities Under the UNFCCC Paris Agreement Article 6.4 Mechanism

In fact, Reference [5] is a document submitted in October 2022 as public comments on **Removal / Sequestration** activities under the UNFCCC **Paris Agreement Article 6 (6.4)** Mechanism. The submitted public comments can be found on this page.

The draft at that time had envisioned the use of tonne-year accounting for quantifying the value of temporary carbon storage. While the public comments targeted the entire information note, not just tonne-year accounting, many organizations ultimately submitted comments expressing concerns about the use of tonne-year accounting.

For example, Carbon Plan, also introduced in Reference [2], strongly commented here that tonne-year accounting should not be permitted. In addition to the comment below, it argued that allowing tonne-year accounting would be inconsistent with recent decisions in the **Voluntary Carbon Market** (tonne-year accounting has also been excluded from **Verra / VCS** and **IC-VCM**'s **Core Carbon Principles**).

Tonne-year accounting should not be authorized under the Article 6.4 Mechanism because it is physically inconsistent with the **Paris Agreement**’s Article 2 goal of temperature stabilization.

Subsequently, public comments were also opened in 2023, and, for example, Microsoft also expressed strong opposition to tonne-year accounting. Ultimately, it was decided that tonne-year accounting would be excluded from the immediate considerations for the **Article 6 (6.4)** Mechanism (link).

After considering options to account for the amounts of carbon stored, and the time it is stored, by activities that remove **Greenhouse Gas**es from the atmosphere, the Supervisory Body agreed to focus on measures that address reversals on a tonne-for-tonne basis and drop tonne-year carbon accounting method from near-term considerations. In explaining the reasons for the decision, the Supervisory Body cited, among other, concerns within the scientific community regarding the underpinning **Methodology**s and assumptions of the tonne-year carbon accounting method as well as insufficient confidence in its suitability for international applications.

Supplement: The Impact of Albedo (Temporary nature-based carbon removal can lower peak warming in a well-below 2 °C scenario)

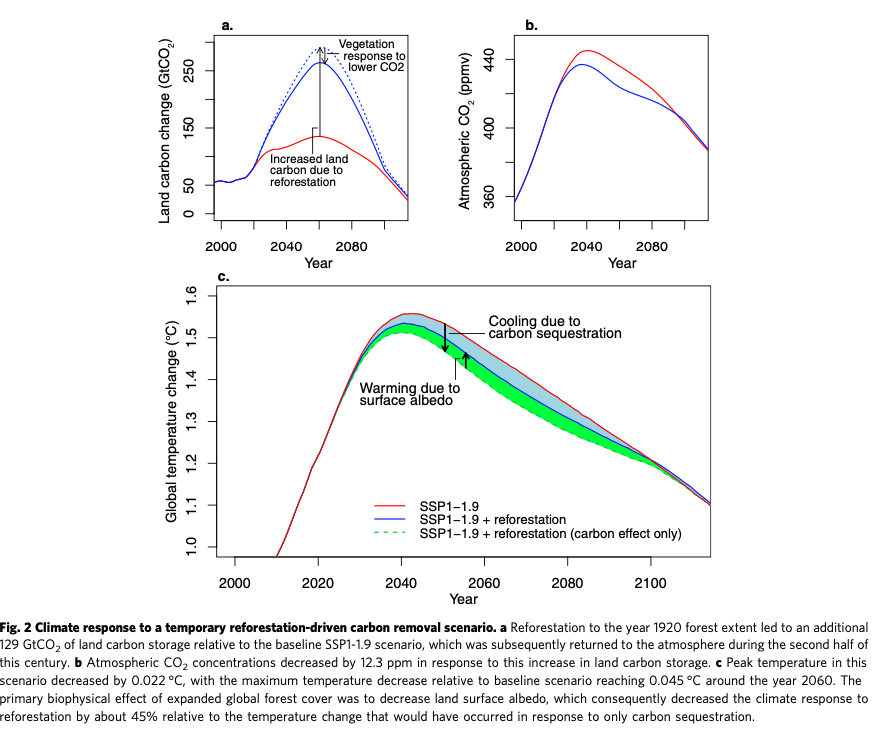

Reference [3], "Temporary nature-based carbon removal can lower peak warming in a well-below 2 °C scenario," presents research results that quantitatively evaluated the contribution of temporary carbon **Removal / Sequestration** by **Nature-based Solutions (NbS)** in the same context as this article. Here, the impact of albedo is also analyzed, so I will introduce it along with an overview.

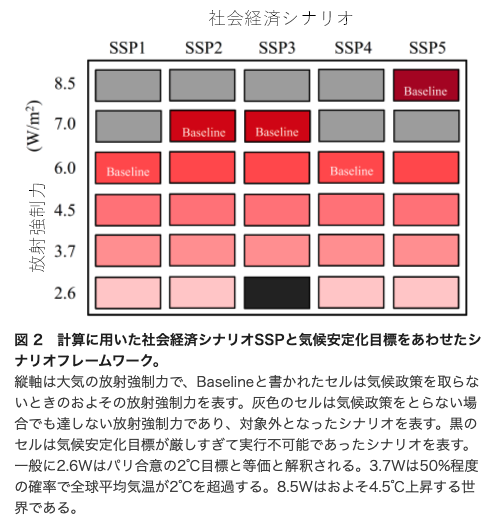

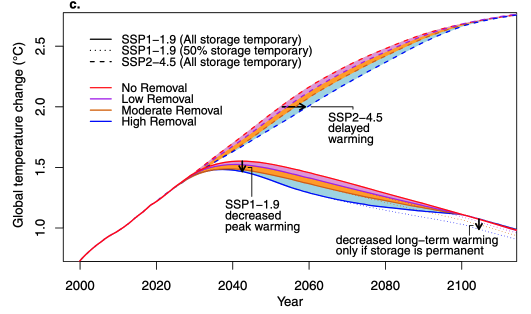

This study used a global climate model with a spatial resolution of 3.6 degrees longitude and 1.8 degrees latitude to examine the temporary carbon **Removal / Sequestration** effect of **NbS** for multiple climate mitigation scenarios defined by Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) and radiative forcing. SSP represents five scenarios (SSP1 to SSP5) along two axes—difficulty of mitigation and difficulty of adaptation—and a scenario framework combining these with climate stabilization targets defined by radiative forcing (e.g., 2.6 W/m^2 is equivalent to the **Paris Agreement** 2°C target, 3.7 means 50% chance of exceeding 2°C, 8.5 means 4.5°C increase) is widely used (for example, refer to this page by the National Institute for Environmental Studies).

The study examined two scenarios within the above SSP and radiative forcing framework: SSP1-1.9 and SSP2-4.5. The overview of each scenario is as follows:

- SSP1-1.9: A very rapid and ambitious future **Emission Reduction** scenario. This scenario assumes socio-economic conditions centered on sustainability principles and rapidly accelerating global climate mitigation efforts, successfully reducing global radiative forcing to 1.9 W/m2 by 2100. CO2 emissions peak in 2020, decrease to **net zero** by 2056, and then become net negative throughout the rest of the century.

- SSP2-4.5: A scenario of relatively weak ongoing efforts. This reflects a middle-of-the-road future socio-economic pathway similar to current global circumstances, where global radiative forcing continues to increase, and mitigation efforts stabilize it at 4.5 W/m2 by 2100. It is a weak climate mitigation scenario where global CO2 emissions peak around 2030-2040 and then decrease (but remain positive in the latter half of the century).

The graph below is considered the most important result of the study. This graph shows the following, consistent with the statement "Impact on Temperature Depends on Cumulative CO₂ Emissions" introduced at the beginning of this article:

Even if carbon storage by **NbS** is temporary and the stored carbon is returned to the atmosphere later in this century4, it still brings climate benefits.

However, a reduction in peak warming levels is only achieved in scenarios (SSP1-1.9) where fossil fuel CO2 emissions rapidly decrease to **net zero**, and as a result, global temperatures peak and then decline during the period when **NbS**-stored carbon is sequestered in nature.

If future mitigation efforts lack this level of stringency (SSP2-4.5), temporary carbon storage based on **NbS** will not affect peak warming, only delay the occurrence of a certain warming level, and offer no long-term climate benefit.

The impact of albedo is clearly illustrated in the figure below. While the increase in carbon stock due to afforestation contributes to suppressing temperature increase, the results show that about half of that contribution is offset by the impact of albedo.

how can something that is better than nothing have nothing to offer a policy target?

Above, we introduced two approaches to valuing temporary carbon storage. Now, let's consider the question posed at the beginning.

Reference [1] states that the answer depends on whether one considers a "**cost-effectiveness**" paradigm or a "**cost-benefit optimization**" paradigm. In the former, policy targets, such as the maximum allowable level of warming above pre-industrial temperatures, are determined through political processes like **Paris Agreement** negotiations. In contrast, the latter attempts to quantify both the costs and **Co-benefits** of climate mitigation and, by comparing these calculations, identify the economically "optimal" level of climate mitigation and global warming. Some studies have even concluded that an optimal scenario could involve a 3°C temperature increase.

Therefore, the answer to the question is: under the "**cost-benefit optimization**" paradigm, **all temporary carbon storage has a non-zero benefit**. However, carbon storage with **durability** below a minimum threshold (i.e., carbon released before peak warming) is not useful for achieving temperature targets and thus **has no value under the cost-effectiveness paradigm**.

Based on the above, how should we consider the use of **Nature-based Carbon Credit**s? As mentioned, if the **durability** is below the minimum threshold, it will not contribute to achieving temperature targets. However, at least under the **cost-benefit optimization** approach, it contributes to suppressing damages caused by temperature increase.

The points explained above are considered to be the basis for concepts like **Beyond Value Chain Mitigation (BVCM)**, proposed for the use of **Carbon Credit**s in **SBTi**, and the idea that permanent **Emission Reduction**s and **Offset**ting with **Carbon Credit**s are not equivalent. It is extremely challenging because the value of temporary carbon storage differs depending on the perspective (the two paradigms mentioned above). Moreover, the minimum threshold for **durability** (which depends on when peak warming occurs) is unknown in advance, nor can it be controlled by a single actor (such as a country or company).

To avoid being swayed by every new guidance when determining decarbonization policies, including the utilization of **Carbon Credit**s within one's own company, it is necessary to follow these foundational discussions as much as possible.

This concludes our introduction to **durability**. Next time, we will introduce the recently proposed PACT Framework.

This was sustainacraft's Newsletter (Special Edition). This newsletter plans to provide information on **NbS** in Japanese approximately bi-weekly to monthly.

Our company profile materials are available here for your reference.

Disclaimers:

This newsletter is not financial advice. So do your own research and due diligence.

Many in this field might associate PACT with the PACT that defines the Pathfinder Framework, but this instance of PACT is unrelated. ↩

The aforementioned 30 times refers to the result when the timescale is taken as 100 years. ↩

We have not found any reference literature on how to express "Tonne-year accounting" in Japanese. Here we use "トン年会計" (tonne-year accounting) in Japanese, but please note that it may not be a common expression. ↩

This corresponds to "All storage temporary" or "50% storage temporary" in the graph. ↩